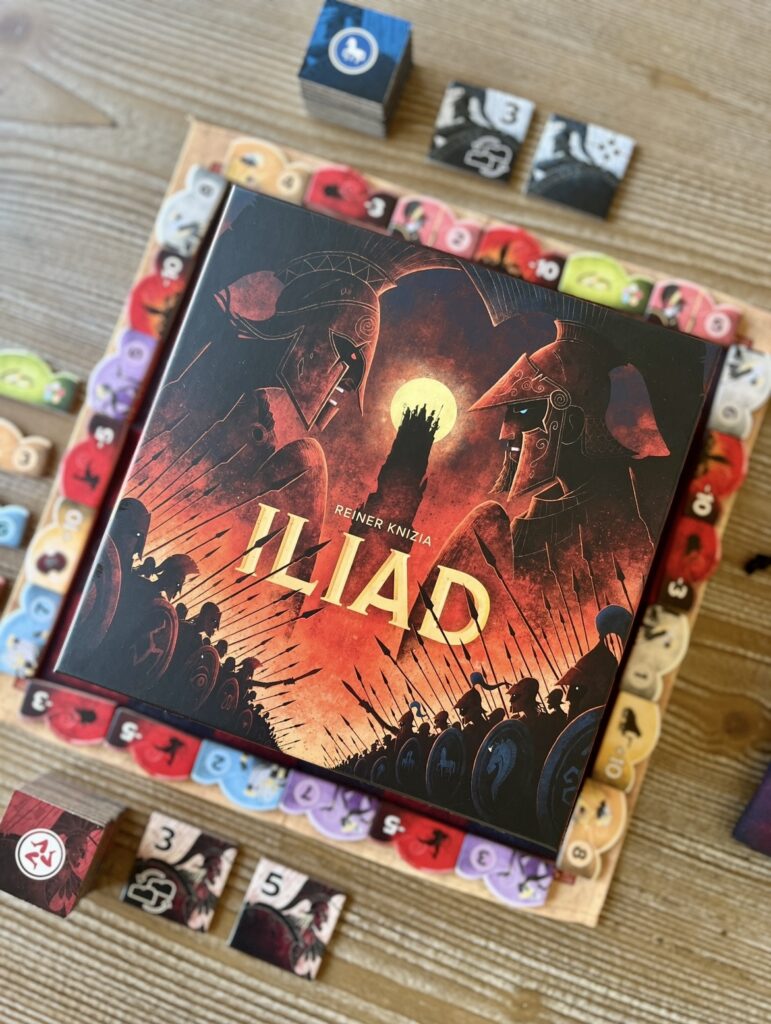

There’s a kind of audacity in how little Iliad gives you to work with. Two tiles and a few powers, all on a modest little grid. That’s the whole game. But inside that tiny box lives one of the tensest, tightest battles I’ve ever had the pleasure of enduring.

Knizia seems to thrive in this zone. The less he gives you, the more dangerous the game is. It doesn’t mess around with multistep turns or economies. It operates on a single axis: pressure. Every move you make is a small push into the grid that echoes outward, affecting each row and column. You’re locked in from the first move, because the game trusts you to find the depth in the smallest decisions.

The board is a 6×6 grid of alternating red and blue checker colors, and you’ll only place tiles on your color. You get a hand of two tiles, drawing off a shuffled stack. After placing a tile (with point values worth 1-5), you then carry out that tile’s effect.

Ones let you reposition an opponent’s tile while twos let you reposition your own. Threes let you swap out one of your collected scoring tokens for another in a small shared market. Fours flip both this tile and the neighboring opponent’s tile. And fives are just big beefy point boys. There’s also something called the Dolos tile, which assumes the value sum of both neighboring tiles.

As soon as a row or column is complete, you score that line by adding up who has the most points. The player that wins gets to choose from the two scoring tiles bordering that line. This may mean you choose a 7 point tile and your opponent gets the 3 point tile. Or, because there are quite a few negative point tiles, your opponent may take that one (*pain*).

Each of the tiles powers is clean, fast, and internalized almost immediately. Within a round or two, you’re thinking it’s like…chess (I’m so sorry, but it’s a rule that every abstract game must be compared to chess. They make you sign a form and everything when you start reviewing).

Not in the “memorize openings” way, but in the way you think ahead a few turns and try to control the board. You can’t think beyond that because of the limited hand and random tile draw deck. And let me tell you, for me this is amazing! Analysis paralysis, that most fear affliction of the modern board gamer, never showed up at our table. It knew it wasn’t invited.

One subtle but crucial rule…if both players have the same point value in a completed line, the last player to place their tile wins the tie. This adds a very interesting strategic layer, especially near the end of the game. Many times you don’t want to be the one placing second to last because it might just hand your opponent the win.

And because it’s Knizia, there’s always a twist. When it comes to winning, you are only eligible to win if you have scoring tokens representing all five of the gods (denoted by different colors). The player who has all five wins. However, if both or neither of you do, it will then come down to point amounts on the tokens themselves. On top of all that, there are two tokens with wedding rings on them. If you manage to win both of those tokens, it then can be used as a sort of wild card for a god. So if you’re missing a color but have both, you’re in the clear.

The main source of frustration I experienced in the game (and I say this primarily so people know that I actually played this game and am not just brainlessly screaming about how amazing it is because someone’s slipped me a Samsonite suitcase stuffed with cash) is drawing the ‘3’ tiles early. If you draw them before you have actually earned a scoring token, the power goes to waste. And I had more than one game in which I drew two or three of the 3’s before getting any tokens! It’s a feature, not a bug, but it caused me mild min-maxing annoyance.

Besides that, what makes the game brilliant is how much you feel with so little. Holding only two tiles is not a constraint…it really is the soul of the game. It denies you comfort because you can’t hoard options or wait for the perfect moment. You play with what you have. You’ll understand the rules in a minute, and then spend the entire game navigating the consequences of those rules.

Contrast that with Ichor, which is still good, but good in a slightly more conventional sense. It has knobs and levers. But in exchange for that texture, it gives up a little clarity. It’s fun, but it doesn’t quite get me the way Iliad does. It doesn’t disappear in your hands the same way. That, I think, is the difference.

I like these deceptively simple Knizia games, what can I say? It’s a game of minimal means and maximum meaning and for my money, a modern Knizia classic.

Thank you to Bitewing Games for the generous review copy