Alright, it’s true that when I pick games to review, I tend to gravitate toward ones I think I’ll actually like. I don’t have a ton of time to wade through half-baked junk in an already oversaturated industry. There have been moments when, in an apparent folie à deux, my husband and I picked a game with mechanics we historically don’t enjoy *cough* pick-up-and-deliver *cough* and, shockingly, we didn’t enjoy it (I’m looking at you, Sand).

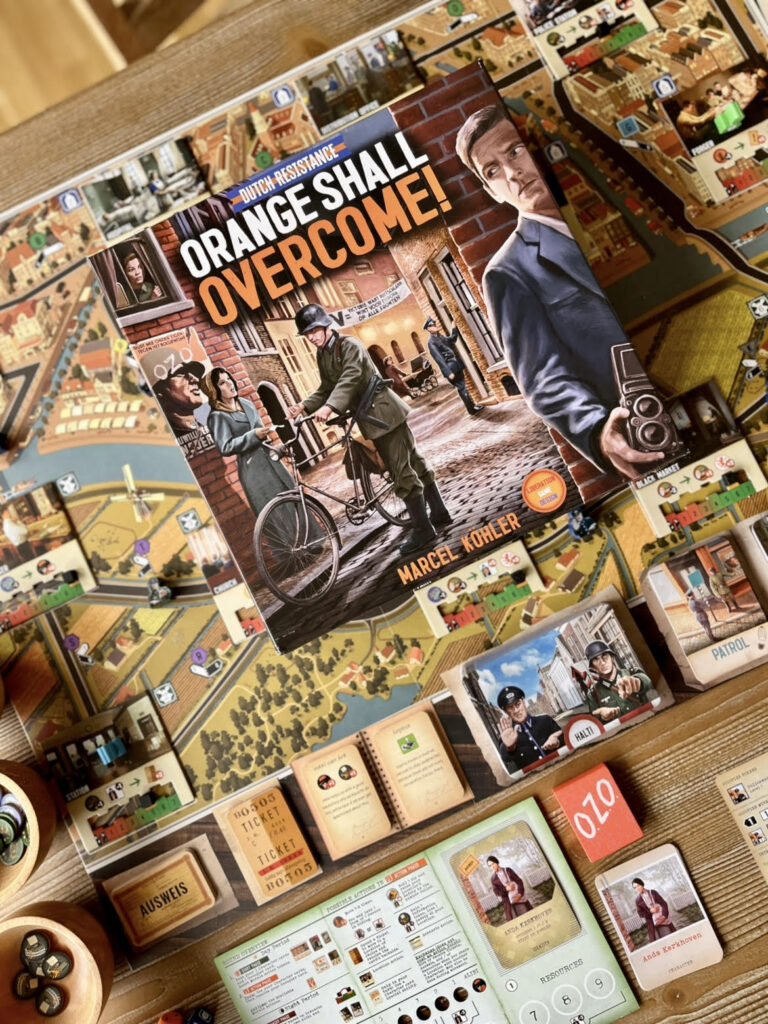

So when I first learned about Dutch Resistance: Orange Shall Overcome!, I was a little cautious. OZO (Oranje Zal Overwinnen, or Orange Shall Overcome in Dutch) is, if you foolishly boil it down to mechanics alone, a pick-up-and-deliver game. But based on how much I loved Undaunted: Stalingrad, War Story: Occupied France, and Halls of Hegra (basically my soft spot being lighter narrative historical games) I had a feeling this wouldn’t be an issue. I love when I’m right.

OZO takes place in the Netherlands during WWII and focuses on resistance fighters pushing back against the German occupation in non-violent ways. It’s scenario-based, with five replayable scenarios that all aim to undermine the German war effort in different ways. You’ll use your asymmetric characters to expand resistance networks, protect people in hiding, move resources and information etc and try to do all of this while staying one step ahead of discovery. Location safety will increase and decrease based on decisions, with the ever-looming potential for a raid. The victories you get are somewhat quiet and provisional.

And I think that’s what impressed me most. This isn’t a game about big climactic moments where everything suddenly clicks into place. It’s much more about persistence, restraint, and sticking with what’s good even when the outcome is uncertain and the cost is real.

That’s a hard thing to pull off in a board game. We tend to imagine resistance (whether historical or personal) as something loud and dramatic. But real resistance is usually repetitive, exhausting, and pretty unglamorous. It doesn’t always look heroic so much as it looks like showing up again tomorrow when you’re already tired. That’s not very Hollywood, but OZO gets this and builds that understanding right into the design, while maintaining gripping gameplay.

The length of the game plays into this in a really intentional way. The standard scenarios can run up to three hours. In another context, that might feel excessive, but here it almost feels like the point. The time investment itself starts to mirror the persistence required to keep going under pressure. It’s engaging the entire game, but the commitment is there. That said, from a realistic game-night perspective, three hours can be a lot, so the designer includes shorter versions of each scenario. The shorter ones I played landed closer to 90 minutes. Personally, I think solo I’ll stick with the longer versions because they pull me deeper into the world, while multiplayer I’m happy to keep things tighter.

Even the pick-up-and-deliver structure feels purposeful. You’re not moving things around for efficiency’s sake. You’re moving people, food, papers, and information under occupation. You’re protecting those in hiding. You’re expanding networks carefully, knowing that every gain also increases the risk of discovery. The rhythm of the game is basically: act, then deal with the fallout.

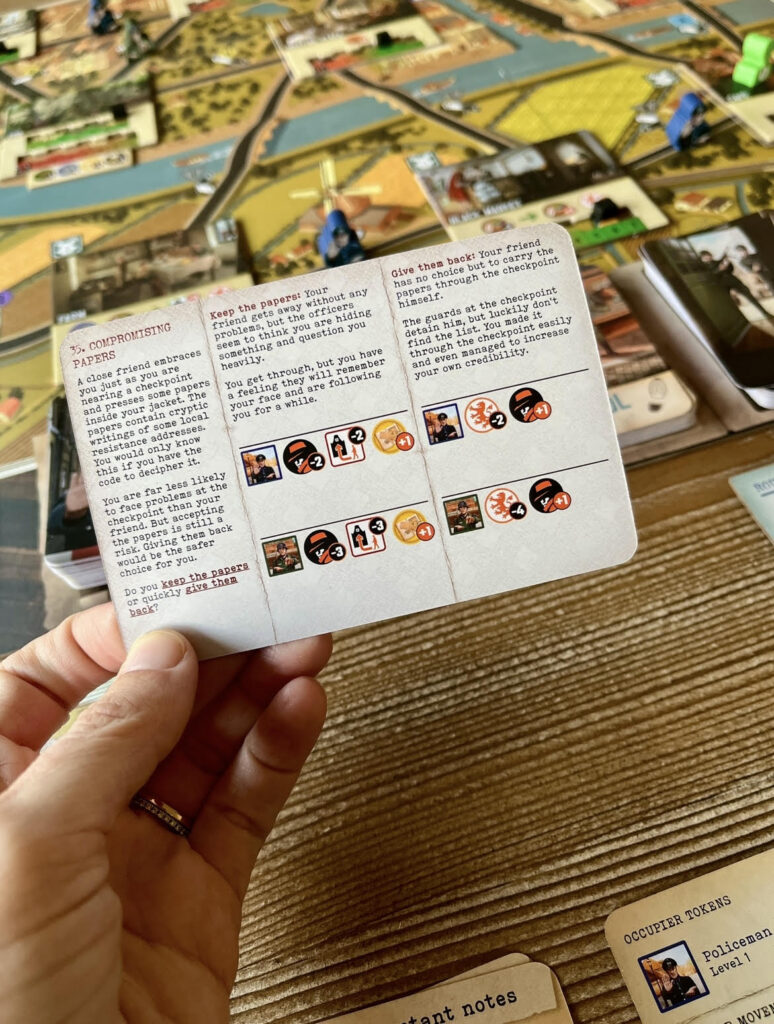

The Halt! cards make this especially clear. Most streets on the map are monitored by police or soldiers, and moving through them usually means drawing a card that presents a specific scenario and a hard choice. You’re deciding with incomplete information, no clear sense of what the “right” answer is, and no guarantee that doing the right thing will actually make things better. Sometimes the safest option weakens the resistance, and sometimes courage just means accepting more trouble. One Halt! card, for example, asks whether you will hide a child trying to escape the Wehrmacht or hand him over. Neither result is particularly beneficial. The game doesn’t reassure you based on the decisions you make, and that feels like the most honest approach. It’s also not meant as a spectacle of struggle. It’s just responsibility, carried by ordinary people.

I’ve never lived under occupation, but I imagine there’s a real temptation toward nihilism in that kind of life. We love hearing the heroic stories in hindsight, but actually living them, without knowing the ending, must feel futile at times, like small actions don’t matter against overwhelming force. What I appreciate about OZO is that it rejects that idea without becoming sentimental. Meaning isn’t found in the decisive victory, but in refusing to surrender the interior life. The resistance exists not because success is guaranteed, but because morality still has weight.

That’s also why the characters work so well. Each one is based on a real resistance fighter, including, in a really lovely and human touch, the designer’s own grandparents. Every character has a specific skill set. One might be better at securing rations, another works at the Station and can travel freely by train without raising suspicion. Every single role feels useful. Success in each game partially comes from learning how to use them together, not from trying to turn any one of them into a hero. This makes perfect sense, especially in a co-op game.

On the more practical side, my biggest question going in was replayability, wondering if five scenarios was enough. I usually just prefer more scenarios over replaying the same ones. But OZO handles replayability quite well. Four different difficulty levels meaningfully change how the game feels, and there’s a large deck of cards that helps keep events unpredictable. You can shorten scenarios, vary starting conditions, and even fully randomize the double-sided board. I replayed Scenario 1 three different times and in different ways without it growing stale.

Maybe it goes without saying at this point, but there’s no doubt this game is tough, even on the easier difficulties. Not Halls of Hegra-level hard at its baseline, but it certainly is thinky and requires effort to win. It’s necessary to plan carefully and adapt constantly. Your wins don’t feel trivial. This challenge makes the game very engaging and satisfying.

But in the end, why do I think about all this extra stuff when it’s just a board game? Obviously I’m taking the game and expanding outwards a bit, but I think that’s a large point of these narrative historical games. They put you under pressure and make you live with the consequences.

Having spent quite a lot of time thinking about hardship in my own life, I know how easily it can overwhelm and consume your attention, even when it looks very different from something like living under occupation. As Viktor Frankl says, suffering expands like a gas, occupying the whole chamber completely. It’s not to compare, but to say that we should take our responses to hardships in our life seriously, because the way we learn to respond to smaller pressures tends to carry over into larger ones. Those habits we form under strain don’t stay contained.

Dutch Resistance: Orange Shall Overcome! lays its focus on responding well. You can’t control everything and you can’t eliminate risk or suffering. You’re never given full clarity about whether what you’re doing will be enough. What you can do is decide how you’ll act in the middle of it…whether you’ll withdraw, or continue to show up and carry responsibility anyway.

That’s what gives the game its weight. It doesn’t ask you to pretend things will turn out well. It asks you to accept the reality of pressure without letting fear dominate your actions. To keep choosing service, cooperation, and care even when the work is unseen and easily undone.

So beyond its engaging and satisfying gameplay, Dutch Resistance: Orange Shall Overcome! gently turns your attention towards endurance, responsibility and how people act under pressure. And in a world and a life where suffering is unavoidable and meaning must be chosen again and again, that feels worth taking seriously.

Thank you to Liberation Game Design for the provided review copy.